Best Exercise for Brain Health of Older Adults

A Guide to Cognitive-Motor Training for the Elderly

Plus, 6 example drills and 3 training sessions you can do at home to improve your brain health!

-

What is Cognitive-Motor Training (CMT)?

Research-Backed Benefits of CMT

Science Behind CMT: Why is it More Effective?

Keys to Effective CMT Design for Older Adults

6 CMT Drills and 3 Sessions You Can Do At Home

References

Everyone will naturally experience cognitive decline as they age. If not addressed, this can significantly impact one’s overall quality of life and even lead to devastating conditions such as dementia. Traditional methods for addressing age-related cognitive decline (like physical exercise and “brain games”) show limitations and varying degrees of effectiveness (Tao, et al. 2022).

Fortunately, scientists have found a more effective solution! An overwhelming amount of new research has shown how performing physical and cognitive training simultaneously, a methodology called cognitive-motor training (also known as cognitive-motor dual-task training), can provide superior brain health benefits compared to performing them separately, making it an essential ingredient for those looking to keep their mind sharp as they age.

Please share with anyone looking to improve their long-term brain health 🧠🙏

Brain health expert Ryan Glatt discusses the benefits of combining physical and cognitive training.

What is Cognitive-Motor Training (CMT)?

Cognitive-motor training involves activities that combine cognitive tasks with physical exercises. There are 3 different ways this combination can occur.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the 3 types of cognitive-motor training (Herold, et al. 2018).

Sequential - The 2 training tasks are performed one after the other (e.g., riding a bike, then sitting down and doing math problems)

Simultaneous (Additional) - The 2 training tasks are combined but NOT dependent on each other (e.g., riding a bike while doing math problems in your head).

Simultaneous (Incorporated) - The 2 training tasks are combined and dependent on each other (e.g., walking in place and stepping in a direction depending on a number that is called).

Research suggests that simultaneous (incorporated) CMT is the most effective approach (Rieker, et al. 2022). Some reasons include:

It’s closer to daily life requirements

Better transfer effects (i.e., improved performance in real-life tasks)

Higher perceived meaningfulness

No task prioritization

More time efficient

More fun and motivating

Research-Backed Benefits of CMT

The scientific evidence on the benefits of utilizing CMT with seniors, particularly in comparison to physical exercise and “brain games” alone, is astonishing. Here, we will highlight some of this groundbreaking research and the 3 key benefits.

1. Greater improvements in physical and cognitive functioning

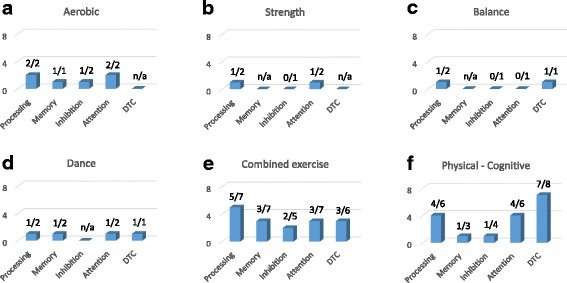

Figure 2. Outcome effects of each of the six types of interventions on cognitive performance gains (from the number of studies) (Levin, et al. 2017).

A systematic review of 50 studies, which included 6,164 healthy older adults, found that performing simultaneous (incorporated) CMT produced the largest gains in executive functions, speed, global cognition, and physical functions when compared to sequential CMT or performing physical and cognitive training separately (Rieker, et al. 2022).

Another systematic review of 19 studies found that CMT improved cognitive functions (executive functions, processing speed, and attention), and dual-task cost significantly more than physical exercise alone (Levin, et al. 2017).

2. Reduced fall risk

A meta-analysis of 7 studies, which included 660 adults over 60, found that reactive step training (which falls under the category of CMT) reduced falls in older adults by approximately 50% (Okubo, et al. 2017).

3. Slowing, or possibly reversing, symptoms of dementia

Researchers at York University’s Faculty of Health found that 30 minutes of CMT once a week can slow the progression of, and possibly reverse, the symptoms of dementia (de Boer, et al. 2018).

Science Behind CMT: Why is it More Effective?

While there are fewer studies that examine the exact mechanisms behind why CMT has these additive effects, there are currently 2 generally recognized explanations.

1. Increased blood flow

Physical exercise increases blood flow to the brain, providing it with essential nutrients and growth factors like BDNF. When combined with simultaneous cognitive challenges, the brain receives these necessary ingredients at an increased rate, leading to accelerated growth (e.g., increased neurogenesis, synapse formation, promotion of cerebral vascular regeneration, and enhanced plasticity in the aging brain) (Tao, et al. 2022).

2. Increased neuron production and survival

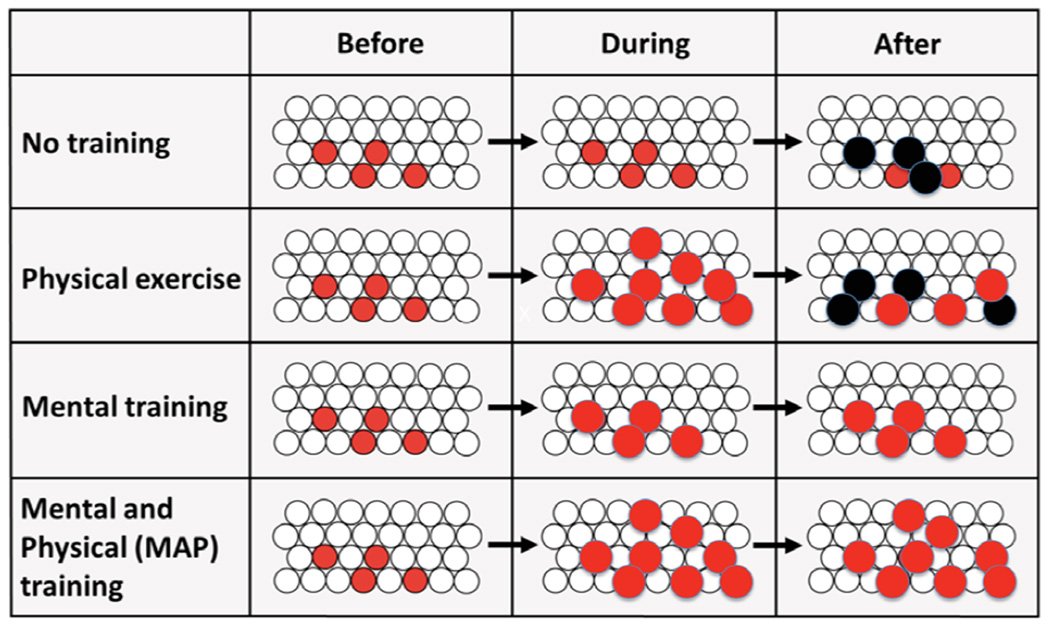

Figure 3. CMT (referred to here as MAP Training) in humans was translated from laboratory studies about neurogenesis in the hippocampus (Shors, et al. 2014)

As illustrated in Figure 3, while physical exercise greatly increases the number of new neurons produced during training, and cognitive training increases the number that survives after training, combining both cognitive and physical training should be more effective at increasing the overall number of neurons that are produced and survive to become mature functioning neurons in the adult brain (Shors, et al. 2014).

Keys to Effective CMT Design for Older Adults

Physical components should include tasks such as stepping, squatting, balancing, gait, strength training, and postural control.

Cognitive components should include tasks that challenge cognitive abilities like processing speed (i.e., reaction time), executive functioning (i.e., decision-making), attention, and working memory.

Adults 60 and older should perform 1-3 CMT sessions per week with sessions ranging from 20-90 minutes to positively improve cognitive functions (Wollesen, et al. 2020).

CMT can be integrated within existing training sessions or as an entirely separate modality.

Keep your training novel and fun by consistently varying the physical and cognitive tasks you use.

Incorporate proper progression, regression, and overload principles.

Make it social - training in a social context provided greater improvements in every physical and cognitive measure (Rieker, et al. 2022).

6 CMT Drills and 3 Sessions You Can Do At Home

Here are 6 CMT drills and 3 sessions older adults can perform using the SwitchedOn Training App and some equipment that’s probably lying around your house.

If you press “TAP TO TRY” while on your mobile device, you will be taken directly to the drill in the app.

Go/No-Go Steps

Colored Arrows

Stand and Tennis Ball Change

Sit and Reach

Ball Memory

Colorful Step-and-Toss

CMT Session Low Intensity 🟢

6 Drills - 35 Minutes

CMT Session Moderate Intensity 🟡

6 Drills - 40 Minutes

CMT Session High Intensity 🔴

6 Drills - 45 Minutes

Download the SwitchedOn App For Free!

-

de Boer, C., Echlin, H. V., Rogojin, A., Baltaretu, B. R., & Sergio, L. E. (2018). Thinking-While-Moving Exercises May Improve Cognition in Elderly with Mild Cognitive Deficits: A Proof-of-Principle Study. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders extra, 8(2), 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1159/000490173

Herold, F., Hamacher, D., Schega, L., & Müller, N. G. (2018). Thinking While Moving or Moving While Thinking - Concepts of Motor-Cognitive Training for Cognitive Performance Enhancement. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 10, 228. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00228

Levin, O., Netz, Y., & Ziv, G. (2017). The beneficial effects of different types of exercise interventions on motor and cognitive functions in older age: a systematic review. European review of aging and physical activity : official journal of the European Group for Research into Elderly and Physical Activity, 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-017-0189-z

Okubo, Y., Schoene, D., & Lord, S. R. (2017). Step training improves reaction time, gait and balance and reduces falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine, 51(7), 586–593. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095452

Rieker, J. A., Reales, J. M., Muiños, M., & Ballesteros, S. (2022). The Effects of Combined Cognitive-Physical Interventions on Cognitive Functioning in Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Multilevel Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 16, 838968. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.838968

Shors, T. J., Olson, R. L., Bates, M. E., Selby, E. A., & Alderman, B. L. (2014). Mental and Physical (MAP) Training: a neurogenesis-inspired intervention that enhances health in humans. Neurobiology of learning and memory, 115, 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2014.08.012

Tao, X., Sun, R., Han, C., & Gong, W. (2022). Cognitive-motor dual task: An effective rehabilitation method in aging-related cognitive impairment. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 14, 1051056. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.1051056

Wollesen, B., Wildbredt, A., van Schooten, K. S., Lim, M. L., & Delbaere, K. (2020). The effects of cognitive-motor training interventions on executive functions in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European review of aging and physical activity : official journal of the European Group for Research into Elderly and Physical Activity, 17, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-020-00240-y